| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

STREAMS Programming Guide |

Part I Application Programming Interface

2. STREAMS Application-Level Components

3. STREAMS Application-Level Mechanisms

4. Application Access to the STREAMS Driver and Module Interfaces

7. STREAMS Framework - Kernel Level

Overview of Streams in Kernel Space

Flow Control in Service Procedures

8. STREAMS Kernel-Level Mechanisms

11. Configuring STREAMS Drivers and Modules

14. Debugging STREAMS-based Applications

B. Kernel Utility Interface Summary

Chapter 3, STREAMS Application-Level Mechanisms discusses messages from the application perspective. The following sections discuss message types, message structure and linkage; how messages are sent and received; and message queues and priority from the kernel perspective.

Several STREAMS messages differ in their purpose and queueing priority. The message types are briefly described and classified, according to their queueing priority, in Table 7-1 and Table 7-2. A detailed discussion of message types is in Chapter 8, STREAMS Kernel-Level Mechanisms.

Some message types are defined as high-priority types. Ordinary or normal messages can have a normal priority of 0, or a priority (also called a band) from 1 to 255.

Table 7-1 Ordinary Messages, Description of Communication Flow

|

Table 7-2 High-Priority Messages, Description of Communication Flow

|

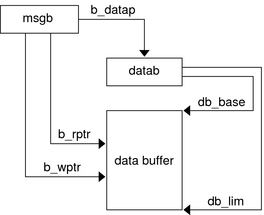

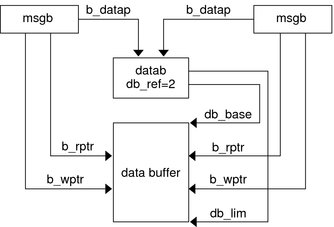

A STREAMS message in its simplest form contains three elements—a message block, a data block, and a data buffer. The data buffer is the location in memory where the actual data of the message is stored. The data block (datab(9S) describes the data buffer—where it starts, where it ends, the message types, and how many message blocks reference it. The message block (msgb(9S)) describes the data block and how the data is used.

The data block has a typedef of dblk_t and has the following public elements:

struct datab {

unsigned char *db_base; /* first byte of buffer */

unsigned char *db_lim; /* last byte+1 of buffer */

unsigned char db_ref; /* msg count ptg to this blk */

unsigned char db_type; /* msg type */

};

typedef struct datab dblk_t;

The datab structure specifies the data buffers' fixed limits (db_base and db_lim), a reference count field (db_ref), and the message type field (db_type). db_base points to the address where the data buffer starts, db_lim points one byte beyond where the data buffer ends, and db_ref maintains a count of the number of message blocks sharing the data buffer.

| Caution - db_base, db_lim, and db_ref should not be modified directly. db_type is modified under carefully monitored conditions, such as changing the message type to reuse the message block. |

In a simple message, the message block references the data block, identifying for each message the address where the message data begins and ends. Each simple message block refers to the data block to identify these addresses, which must be within the confines of the buffer such that db_base ≥ b_rptr ≥≥ b_wptr ≥ db_lim. For ordinary messages, a priority band can be indicated, and this band is used if the message is queued.

Figure 7-1 shows the linkages between msgb, datab, and the data buffer in a simple message.

Figure 7-1 Simple Message Referencing the Data Block

The message block (see msgb(9S)) has a typedef of mblk_t and has the following public elements:

struct msgb {

struct msgb *b_next; /*next msg in queue*/

struct msgb *b_prev; /*previous msg in queue*/

struct msgb *b_cont; /*next msg block of message*/

unsigned char *b_rptr; /*1st unread byte in bufr*/

unsigned char *b_wptr; /*1st unwritten byte in bufr*/

struct datab *b_datap; /*data block*/

unsigned char b_band; /*message priority*/

unsigned short b_flag; /*message flags*/

};

The STREAMS framework uses the b_next and b_prev fields to link messages into queues. b_rptr and b_wptr specify the current read and write pointers respectively, in the data buffer pointed to by b_datap. The fields b_rptr and b_wptr are maintained by drivers and modules.

The field b_band specifies a priority band where the message is placed when it is queued using the STREAMS utility routines. This field has no meaning for high-priority messages and is set to zero for these messages. When a message is allocated using allocb(9F), the b_band field is initially set to zero. Modules and drivers can set this field to a value from 0 to 255 depending on the number of priority bands needed. Lower numbers represent lower priority. The kernel incurs overhead in maintaining bands if nonzero numbers are used.

| Caution - Message block data elements must not modify b_next, b_prev, or b_datap. The first two fields are modified by utility routines such as putq(9F) and getq(9F). Message block data elements can modify b_cont, b_rptr, b_wptr, b_band (for ordinary messages types), and b_flag. |

The SunOS environment places b_band in the msgb structure. Some other STREAMS implementations place b_band in the datab structure. The SunOS implementation is more flexible because each message is independent. For shared data blocks, the b_band can differ in the SunOS implementation, but not in other implementations.

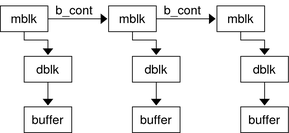

A complex message can consist of several linked message blocks. If buffer size is limited or if processing expands the message, multiple message blocks are formed in the message, as shown in Figure 7-2. When a message is composed of multiple message blocks, the type associated with the first message block determines the overall message type, regardless of the types of the attached message blocks.

Figure 7-2 Linked Message Blocks

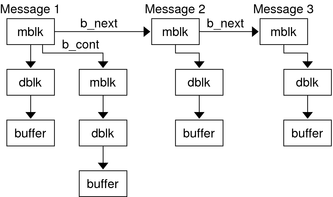

A put procedure processes single messages immediately and can pass the message to the next module's put procedure using put or putnext. Alternatively, the message is linked on the message queue for later processing, to be processed by a module's service procedure (putq(9F)). Note that only the first module of a set of linked modules is linked to the next message in the queue.

Think of linked message blocks as a concatenation of messages. Queued messages are a linked list of individual messages that can also be linked message blocks.

In Figure 7-3 messages are queued: Message 1 being the first message on the queue, followed by Message 2 and Message 3. Notice that Message 1 is a linked message consisting of more than one mblk.

| Caution - Modules or drivers must not modify b_next and b_prev. These fields are modified by utility routines such as putq(9F) and getq(9F). |

In Figure 7-4, two message blocks are shown pointing to one data block. db_ref indicates that there are two references (mblks) to the data block. db_base and db_lim point to an address range in the data buffer. The b_rptr and b_wptr of both message blocks must fall within the assigned range specified by the data block.

Data blocks are shared using utility routines (see dupmsg(9F) or dupb(9F)). STREAMS maintains a count of the message blocks sharing a data block in the db_ref field.

These two mblks share the same data and datablock. If a module changes the contents of the data or message type, it is visible to the owner of the message block.

When modifying data contained in the dblk or data buffer, if the reference count of the message is greater than one, the module should copy the message using copymsg(9F), free the duplicated message, and then change the appropriate data.

Note - Hardening Information. At Sun, it is assumed that a message with a db_ref > 1 is a “read-only” message and can be read but not modified. If the module wishes to modify the data, it should first copy the message, and free the original:

if ( dbp->db_ref > 1 ) {

dblk_t *newdbp;

/* Get a copy of the message */

newdbp = copymsg(dbp);

/* Free the original */

freemsg(dbp);

/* make sure that we are now using the new dbp */

dbp = newdbp;

}

STREAMS provides utility routines and macros (identified in Appendix B, Kernel Utility Interface Summary) to assist in managing messages and message queues, and in other areas of module and driver development. Always use utility routines to operate on a message queue or to free or allocate messages. If messages are manipulated in the queue without using the STREAMS utilities, the message ordering can become confused and cause inconsistent results.

Among the message types, the most commonly used messages are M_DATA, M_PROTO, and M_PCPROTO. These messages can be passed between a process and the topmost module in a stream, with the same message boundary alignment maintained between user and kernel space. This allows a user process to function, to some degree, as a module above the stream and maintain a service interface. M_PROTO and M_PCPROTO messages carry service interface information among modules, drivers, and user processes.

Modules and drivers do not interact directly with any interfaces except open(2) and close(2). The stream head translates and passes all messages between user processes and the uppermost STREAMS module. Message transfers between a process and the stream head can occur in different forms. For example, M_DATA and M_PROTO messages can be transferred in their direct form by getmsg(2) and putmsg(2). Alternatively, write(2) creates one or more M_DATA messages from the data buffer supplied in the call. M_DATA messages received at the stream head are consumed by read(2) and copied into the user buffer.

Any module or driver can send any message in either direction on a stream. However, based on their intended use in STREAMS and their treatment by the stream head, certain messages can be categorized as upstream, downstream, or bidirectional. For example, M_DATA, M_PROTO, or M_PCPROTO messages can be sent in both directions. Other message types such as M_IOACK are sent upstream to be processed only by the stream head. Messages to be sent downstream are silently discarded if received by the stream head. Table 7-1 and Table 7-2 indicate the intended direction of message types.

STREAMS enables modules to create messages and pass them to neighboring modules. read(2) and write(2) are not enough to enable a user process to generate and receive all messages. In the first place, read(2) and write(2) are byte-stream oriented with no concept of message boundaries. The message boundary of each service primitive must be preserved so that the start and end of each primitive can be located in order to support service interfaces. Furthermore, read(2) and write(2) offer only one buffer to the user for transmitting and receiving STREAMS messages. If control information and data is placed in a single buffer, the user has to parse the contents of the buffer to separate the data from the control information. Furthermore, read(2) and write(2) offer only one buffer to the user for transmitting and receiving STREAMS messages. If control information and data is placed in a single buffer, the user has to parse the contents of the buffer to separate the data from the control information.

getmsg(2) and putmsg(2) enable a user process and the stream to pass data and control information between one another while maintaining distinct message boundaries.

Note - Hardening Information. There is no guarantee in STREAMS that a b_rptr or b_wptr will fall on a proper bit alignment. Most modules that pass data structures with pointers try to retain the desired bit alignment. If the module is in a stream where this is reasonably guaranteed, it does not need to check data alignment. However, for the purpose of hardening, modules that are concerned about data alignment should verify that pointers are properly aligned, or copy data in mblks to local structures that are properly aligned (see bcopy(3C)).

Note - Hardening Information. Ensure that the changing of pointers is uniform (b_rptr <= b_rptr). Keep pointers inside db_base and db_lim. It is easier to recover from an error if b_rptr and b_wptr are inside db_base and db_lim.

When a module changes the b_rptr and/or the b_wptr, it should verify the following relationship:

db_base <= b_rptr <= b_wptr <= db_lim

and

db_base < db_lim

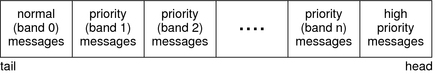

Message queues grow when the STREAMS scheduler is delayed from calling a service procedure by system activity, or when the procedure is blocked by flow control. When called by the scheduler, a module's service procedure processes queued messages in a FIFO manner (getq(9F)). However, some messages associated with certain conditions, such as M_ERROR, must reach their stream destination as rapidly as possible. This is accomplished by associating priorities with the messages. These priorities imply a certain ordering of messages in the queue, as shown in Figure 7-5.

Each message has a priority band associated with it. Ordinary messages have a priority band of zero. The priority band of high-priority messages is ignored since they are high priority and thus not affected by flow control. putq(9F) places high-priority messages at the head of the message queue, followed by priority band messages (expedited data) and ordinary messages.

Figure 7-5 Message Ordering in a Queue

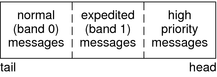

When a message is queued, it is placed after the messages of the same priority already in the queue (in other words, FIFO within their order of queueing). This affects the flow-control parameters associated with the band of the same priority. Message priorities range from 0 (normal) to 255 (highest). This provides up to 256 bands of message flow within a stream. An example of how to implement expedited data would be with one extra band of data flow (priority band 1), is shown in the following figure. Queues are explained in detail in the next section.

Figure 7-6 Message Ordering with One Priority Band

High-priority messages are not subject to flow control. When they are queued by putq(9F), the associated queue is always scheduled, even if the queue has been disabled (noenable(9F)). When the service procedure is called by the stream's scheduler, the procedure uses getq(9F) to retrieve the first message on queue, which is a high-priority message. Service procedures must be implemented to act on high-priority messages immediately. The mechanisms just mentioned—priority message queueing, absence of flow control, and immediate processing by a procedure—result in rapid transport of high-priority messages between the originating and destination components in the stream.

In general, high-priority messages should be processed immediately by the module's put procedure and not placed on the service queue.