14 Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

This chapter includes the following sections:

- Cache Layers

The Partitioned (Distributed) cache service in Coherence has three distinct layers that are used for data storage. - Local Storage

Local storage refers to the data structures that actually store or cache the data that is managed by Coherence. - Operations

There are number of operation types performed against a backing map. - Capacity Planning

The total amount of data placed into the data grid must not exceed some predetermined amount of memory. - Using Partitioned Backing Maps

Coherence provides a partitioned backing map implementation that differs from the default backing map implementation. - Using the Elastic Data Feature to Store Data

The Elastic Data feature is used to seamlessly store data across memory and disk-based devices. - Using Asynchronous Backup

Distributed caches support both synchronous and asynchronous backup. - Using the Read Locator

Currently Coherence requests are serviced by the primary owner of the associated partition(s) (ignoring the client side cachesNearCacheandContinuousQueryCache). Coherence 14.1.1.2206 introduces the read-locator feature. Read locator allows for certain requests to be targeted to non-primary partition owners (backups) to balance request load or reduce latency. - Scheduling Backups

Coherence provides an ability for applications to favor the write throughput over the coherent backup copies (async-backup). This can result in acknowledged write requests being lost if they are not successfully backed up. - Using Asynchronous Persistence

Asynchronous persistence mode allows the storage servers to persist data asynchronously, thus a mutating request is successful once the primary stores the data and (if there is a synchronous backup) once the backup receives the update. - Using Persistent Backups

Coherence 14.1.1.2206 adds a new persistence mode that stores backup partitions on disk as additional copies of persisted primary ones. - Using Delta Backup

Delta backup is a technique that is used to apply changes to a backup binary entry rather than replacing the whole entry when the primary entry changes. - Integrating Caffeine

Coherence 14.1.1.2206 adds a Caffeine backing map implementation, enabling you to use Caffeine wherever the standard Coherence local cache can be used: as a local cache, as a backing map for a partitioned cache, or as a front map for a near cache.

Parent topic: Using Caches

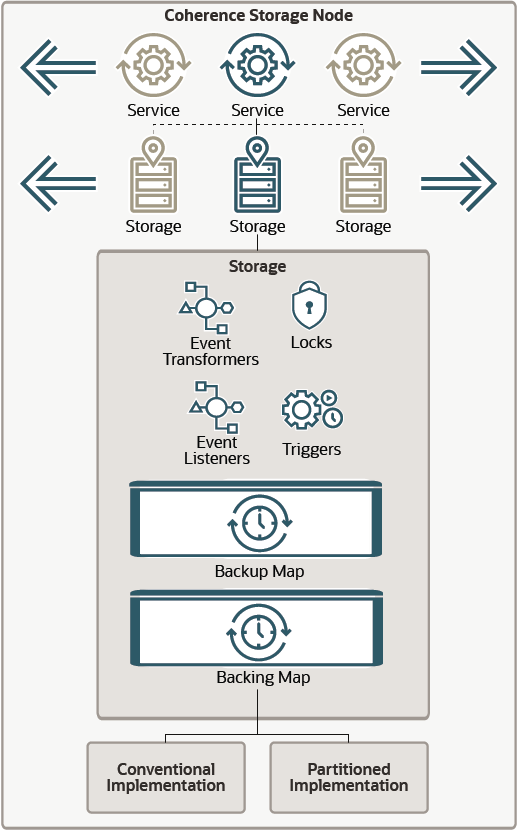

Cache Layers

-

Client View – The client view represents a virtual layer that provides access to the underlying partitioned data. Access to this tier is provided using the

NamedCacheinterface. In this layer you can also create synthetic data structures such asNearCacheorContinuousQueryCache. -

Storage Manager – The storage manager is the server-side tier that is responsible for processing cache-related requests from the client tier. It manages the data structures that hold the actual cache data (primary and backup copies) and information about locks, event listeners, map triggers, and so on.

-

Backing Map – The Backing Map is the server-side data structure that holds actual data.

Coherence allows users to configure out-of-the-box and custom backing map implementations. The only constraint for a Map implementation is the understanding that the Storage Manager provides all keys and values in internal (Binary) format. To deal with conversions of that internal data to and from an Object format, the Storage Manager can supply Backing Map implementations with a BackingMapManagerContext reference.

Figure 14-1 shows a conceptual view of backing maps.

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Local Storage

java.util.Map. When a local storage implementation is used by Coherence to store replicated or distributed data, it is called a backing map because Coherence is actually backed by that local storage implementation. The other common uses of local storage is in front of a distributed cache and as a backup behind the distributed cache.

Caution:

Be careful when using any backing map that does not store data on heap, especially if storing more data than can actually fit on heap. Certain cache operations (for example, unindexed queries) can potentially traverse a large number of entries that force the backing map to bring those entries onto the heap. Also, partition transfers (for example, restoring from backup or transferring partition ownership when a new member joins) force the backing map to bring lots of entries onto the heap. This can cause GC problems and potentially lead to OutOfMemory errors.

Coherence supports the following local storage implementations:

-

Safe HashMap: This is the default lossless implementation. A lossless implementation is one, like the Java

Hashtableclass, that is neither size-limited nor auto-expiring. In other words, it is an implementation that never evicts ("loses") cache items on its own. This particularHashMapimplementation is optimized for extremely high thread-level concurrency. For the default implementation, use classcom.tangosol.util.SafeHashMap; when an implementation is required that provides cache events, usecom.tangosol.util.ObservableHashMap. These implementations are thread-safe. -

Local Cache: This is the default size-limiting and auto-expiring implementation. See Capacity Planning. A local cache limits the size of the cache and automatically expires cache items after a certain period. For the default implementation, use

com.tangosol.net.cache.LocalCache; this implementation is thread safe and supports cache events,com.tangosol.net.CacheLoader,CacheStoreand configurable/pluggable eviction policies. -

Read/Write Backing Map: This is the default backing map implementation for caches that load from a backing store (such as a database) on a cache miss. It can be configured as a read-only cache (consumer model) or as either a write-through or a write-behind cache (for the consumer/producer model). The write-through and write-behind modes are intended only for use with the distributed cache service. If used with a near cache and the near cache must be kept synchronous with the distributed cache, it is possible to combine the use of this backing map with a Seppuku-based near cache (for near cache invalidation purposes). For the default implementation, use class

com.tangosol.net.cache.ReadWriteBackingMap. -

Binary Map (Java NIO): This is a backing map implementation that can store its information outside of the Java heap in memory-mapped files, which means that it does not affect the Java heap size and the related JVM garbage-collection performance that can be responsible for application pauses. This implementation is also available for distributed cache backups, which is particularly useful for read-mostly and read-only caches that require backup for high availability purposes, because it means that the backup does not affect the Java heap size yet it is immediately available in case of failover.

-

Serialization Map: This is a backing map implementation that translates its data to a form that can be stored on disk, referred to as a serialized form. It requires a separate

com.tangosol.io.BinaryStoreobject into which it stores the serialized form of the data. Serialization Map supports any custom implementation ofBinaryStore. For the default implementation of Serialization Map, usecom.tangosol.net.cache.SerializationMap. -

Serialization Cache: This is an extension of the

SerializationMapthat supports an LRU eviction policy. For example, a serialization cache can limit the size of disk files. For the default implementation of Serialization Cache, usecom.tangosol.net.cache.SerializationCache. -

Journal: This is a backing map implementation that stores data to either RAM, disk, or both RAM and disk. Journaling use the

com.tangosol.io.journal.JournalBinaryStoreclass. See Using the Elastic Data Feature to Store Data. -

Overflow Map: An overflow map does not actually provide storage, but it deserves mention in this section because it can combine two local storage implementations so that when the first one fills up, it overflows into the second. For the default implementation of

OverflowMap, usecom.tangosol.net.cache.OverflowMap. - Custom Map: This is a backing map implementation that conforms

to the

java.util.Mapinterface.For example:

<backing-map-scheme> <class-scheme> <class-name>com.tangosol.util.SafeHashMap</class-name> </class-scheme> </backing-map-scheme>Note:

Irrespective of the backing map implementation you use, the map must be thread safe.

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Operations

-

Natural access and update operations caused by the application usage. For example,

NamedCache.get()call naturally causes aMap.get()call on a corresponding Backing Map; theNamedCache.invoke()call may cause a sequence ofMap.get()followed by theMap.put(); theNamedCache.keySet(filter)call may cause anMap.entrySet().iterator()loop, and so on. -

Remove operations caused by the time-based expiry or the size-based eviction. For example, a

NamedCache.get()orNamedCache.size()call from the client tier could cause aMap.remove()call due to an entry expiry timeout; orNamedCache.put()call causing someMap.remove()calls (for different keys) caused by the total amount data in a backing map reaching the configured high water-mark value. -

Insert operations caused by a

CacheStore.load()operation (for backing maps configured with read-through or read-ahead features) -

Synthetic access and updates caused by the partition distribution (which in turn could be caused by cluster nodes fail over or fail back). In this case, without any application tier call, some entries could be inserted or removed from the backing map.

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Capacity Planning

The total amount of data held in a Coherence cache equals the sum of data volume in all corresponding backing maps (one per each cluster node that runs the corresponding partitioned cache service in a storage enabled mode).

Consider the following cache configuration excerpts:

<backing-map-scheme> <local-scheme/> </backing-map-scheme>

The backing map above is an instance of

com.tangosol.net.cache.LocalCache and does not have any pre-determined size

constraints and has to be controlled explicitly. Failure to do so could cause the JVM to go

out-of-memory. The following example configures size constraints on the backing map:

<backing-map-scheme>

<local-scheme>

<eviction-policy>LRU</eviction-policy>

<high-units>100M</high-units>

<unit-calculator>BINARY</unit-calculator>

</local-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>This backing map above is also a

com.tangosol.net.cache.LocalCache and has a capacity limit of 100MB. If no

unit is specified in <high-units>, the default is byte. See <high-units>. You can also specify a

<unit-factor>, as shown in the following example:

<backing-map-scheme>

<local-scheme>

<eviction-policy>LRU</eviction-policy>

<high-units>100</high-units>

<unit-calculator>BINARY</unit-calculator>

<unit-factor>1000000</unit-factor>

</local-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>As the total amount of data held by this backing map exceeds that high watermark,

some entries are removed from the backing map, bringing the volume down to the low watermark

value (<low-units> configuration element, which defaults to 80% of the

<high-units>). If the value exceeds

Integer.MAX_VALUE, then a unit factor is automatically used and the value

for <high-units> and <low-units> are adjusted

accordingly. The choice of the removed entries is based on the LRU (Least Recently Used)

eviction policy. Other options are LFU (Least Frequently Used) and Hybrid (a combination of

LRU and LFU).

The following backing map automatically evicts any entries that have not been

updated for more than an hour. Entries that exceed one hour are not returned to a caller and

are lazily removed from the cache when the next cache operation is performed or the next

scheduled daemon EvictionTask is run. The EvictionTask

daemon schedule depends on the cache expiry delay. The minimum interval is 250ms.

<backing-map-scheme>

<local-scheme>

<expiry-delay>1h</expiry-delay>

</local-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>A backing map within a distributed scheme also supports sliding expiry. If enabled:

-

Read operations extend the expiry of the accessed cache entries. The read operations include

get,getAll,invokeandinvokeAllwithout mutating the entries (for example, onlyentry.getValuein an entry processor). -

Any enlisted entries that are not mutated (for example, from interceptors or triggers) are also expiry extended.

-

The backup (for expiry change) is done asynchronously if the operation is read access only. If a mutating operation is involved (for example, an eviction occurred during a

putor aputAlloperation), then the backup is done synchronously.

Note:

Sliding expiry is not performed for entries that are accessed based on query requests likeaggregate and

query operations.

To enable sliding expiry, set the <sliding-expiry>

element, within a <backing-map-scheme> element to true

and ensure that the <expiry-delay> element is set to a value greater

than zero. For example,

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>dist-expiry</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedExpiry</service-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<sliding-expiry>true</sliding-expiry>

<local-scheme>

<expiry-delay>3s</expiry-delay>

</local-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>

</distributed-scheme>

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Using Partitioned Backing Maps

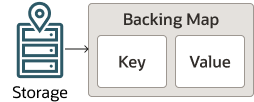

Figure 14-2 shows a conceptual view of the conventional backing map implementation.

Figure 14-2 Conventional Backing Map Implementation

Description of "Figure 14-2 Conventional Backing Map Implementation"

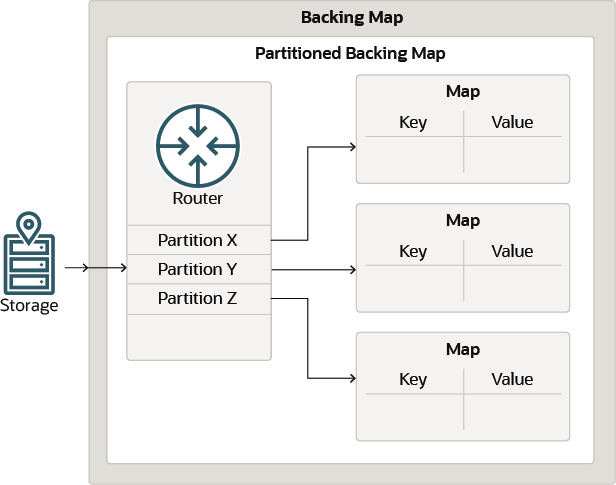

A partitioned backing map is a multiplexer of actual Map implementations, each of which contains only entries that belong to the same partition. Partitioned backing maps raise the storage limit (induced by the java.util.Map API) from 2G for a backing map to 2G for each partition. Partitioned backing maps are typically used whenever a solution may reach the 2G backing map limit, which is often possible when using the elastic data feature. See Using the Elastic Data Feature to Store Data.

Figure 14-3 shows a conceptual view of the partitioned backing map implementation.

Figure 14-3 Partitioned Backing Map Implementation

Description of "Figure 14-3 Partitioned Backing Map Implementation"

To configure a partitioned backing map, add a <partitioned> element with a value of true. For example:

<backing-map-scheme>

<partitioned>true</partitioned>

<external-scheme>

<nio-file-manager>

<initial-size>1MB</initial-size>

<maximum-size>50MB</maximum-size>

</nio-file-manager>

<high-units>8192</high-units>

<unit-calculator>BINARY</unit-calculator>

</external-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>

This backing map is an instance of com.tangosol.net.partition.PartitionSplittingBackingMap, with individual partition holding maps being instances of com.tangosol.net.cache.SerializationCache that each store values in the extended (nio) memory. The individual nio buffers have a limit of 50MB, while the backing map as whole has a capacity limit of 8GB (8192*1048576).

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Using the Elastic Data Feature to Store Data

Elastic data contains two distinct components: the RAM journal for storing data in-memory and the flash journal for storing data to disk-based devices. These can be combined in different combinations and are typically used for backing maps and backup storage but can also be used with composite caches (for example, a near cache). The RAM journal can work with the flash journal to enable seamless overflow to disk.

Caches that use RAM and flash journals are configured as part of a cache scheme definition within a cache configuration file. Journaling behavior is configured, as required, by using an operational override file to override the out-of-box configuration.

This section includes the following topics:

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Journaling Overview

Journaling refers to the technique of recording state changes in a sequence of modifications called a journal. As changes occur, the journal records each value for a specific key and a tree structure that is stored in memory keeps track of which journal entry contains the current value for a particular key. To find the value for an entry, you find the key in the tree which includes a pointer to the journal entry that contains the latest value.

As changes in the journal become obsolete due to new values being written for a key, stale values accumulate in the journal. At regular intervals, the stale values are evacuated making room for new values to be written in the journal.

The Elastic Data feature includes a RAM journal implementation and a Flash journal implementation that work seamlessly with each other. If for example the RAM Journal runs out of memory, the Flash Journal can automatically accept the overflow from the RAM Journal, allowing for caches to expand far beyond the size of RAM.

Note:

Elastic data is ideal when performing key-based operations and typically not recommend for large filter-based operations. When journaling is enabled, additional capacity planning is required if you are performing data grid operations (such as queries and aggregations) on large result sets. See General Guidelines in Administering Oracle Coherence.

A resource manager controls journaling. The resource manager creates and utilizes a binary store to perform operations on the journal. The binary store is implemented by the JournalBinaryStore class. All reads and writes through the binary store are handled by the resource manager. There is a resource manager for RAM journals (RamJournalRM) and one for flash journals (FlashJournalRM).

Parent topic: Using the Elastic Data Feature to Store Data

Defining Journal Schemes

The <ramjournal-scheme> and <flashjournal-scheme> elements are used to configure RAM and Flash journals (respectively) in a cache configuration file. See ramjournal-scheme and flashjournal-scheme.

This section includes the following topics:

- Configuring a RAM Journal Backing Map

- Configuring a Flash Journal Backing Map

- Referencing a Journal Scheme

- Using Journal Expiry and Eviction

- Using a Journal Scheme for Backup Storage

- Enabling a Custom Map Implementation for a Journal Scheme

Parent topic: Using the Elastic Data Feature to Store Data

Configuring a RAM Journal Backing Map

To configure a RAM journal backing map, add the <ramjournal-scheme> element within the <backing-map-scheme> element of a cache definition. The following example creates a distributed cache that uses a RAM journal for the backing map. The RAM journal automatically delegates to a flash journal when the RAM journal exceeds the configured memory size. See Changing Journaling Behavior.

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>distributed-journal</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedCacheRAMJournal</service-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<ramjournal-scheme/>

</backing-map-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme>

Parent topic: Defining Journal Schemes

Configuring a Flash Journal Backing Map

To configure a flash journal backing map, add the <flashjournal-scheme> element within the <backing-map-scheme> element of a cache definition. The following example creates a distributed scheme that uses a flash journal for the backing map.

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>distributed-journal</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedCacheFlashJournal</service-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<flashjournal-scheme/>

</backing-map-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme>

Parent topic: Defining Journal Schemes

Referencing a Journal Scheme

The RAM and flash journal schemes both support the use of scheme references to reuse scheme definitions. The following example creates a distributed cache and configures a RAM journal backing map by referencing the RAM scheme definition called default-ram.

<caching-schemes>

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>distributed-journal</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedCacheJournal</service-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<ramjournal-scheme>

<scheme-ref>default-ram</scheme-ref>

</ramjournal-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme>

<ramjournal-scheme>

<scheme-name>default-ram</scheme-name>

</ramjournal-scheme>

</caching-schemes>

Parent topic: Defining Journal Schemes

Using Journal Expiry and Eviction

The RAM and flash journal can be size-limited. They can restrict the number of entries to store and automatically evict entries when the journal becomes full. Furthermore, both the sizing of entries and the eviction policies can be customized. The following example defines expiry and eviction settings for a RAM journal:

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>distributed-journal</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedCacheFlashJournal</service-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<ramjournal-scheme>

<eviction-policy>LFU</eviction-policy>

<high-units>100</high-units>

<low-units>80</low-units>

<unit-calculator>Binary</unit-calculator>

<expiry-delay>0</expiry-delay>

</ramjournal-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme>

Parent topic: Defining Journal Schemes

Using a Journal Scheme for Backup Storage

Journal schemes are used for backup storage as well as for backing maps. By default, Flash Journal is used as the backup storage. This default behavior can be modified by explicitly specifying the storage type within the <backup-storage> element. The following configuration uses a RAM journal for the backing map and explicitly configures a RAM journal for backup storage:

<caching-schemes>

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>default-distributed-journal</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedCacheJournal</service-name>

<backup-storage>

<type>scheme</type>

<scheme-name>example-ram</scheme-name>

</backup-storage>

<backing-map-scheme>

<ramjournal-scheme/>

</backing-map-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme>

<ramjournal-scheme>

<scheme-name>example-ram</scheme-name>

</ramjournal-scheme>

</caching-schemes>

Parent topic: Defining Journal Schemes

Enabling a Custom Map Implementation for a Journal Scheme

Journal schemes can be configured to use a custom backing map as required. Custom map implementations must extend the CompactSerializationCache class and declare the exact same set of public constructors.

To enable, a custom implementation, add a <class-scheme> element whose value is the fully qualified name of the custom class. Any parameters that are required by the custom class can be defined using the <init-params> element. The following example enables a custom map implementation called MyCompactSerializationCache.

<flashjournal-scheme> <scheme-name>example-flash</scheme-name> <class-name>package.MyCompactSerializationCache</class-name> </flashjournal-scheme>

Parent topic: Defining Journal Schemes

Changing Journaling Behavior

A resource manager controls journaling behavior. There is a resource manager for RAM journals (RamJournalRM) and a resource manager for Flash journals (FlashJournalRM). The resource managers are configured for a cluster in the tangosol-coherence-override.xml operational override file. The resource managers' default out-of-box settings are used if no configuration overrides are set.

This section includes the following topics:

Parent topic: Using the Elastic Data Feature to Store Data

Configuring the RAM Journal Resource Manager

The <ramjournal-manager> element is used to configure RAM journal behavior. The following list summarizes the default characteristics of a RAM journal. See ramjournal-manager.

-

Binary values are limited by default to 64KB (and a maximum of 4MB). A flash journal is automatically used if a binary value exceeds the configured limit.

-

An individual buffer (a journal file) is limited by default to 2MB (and a maximum of 2GB). The maximum file size should not be changed.

-

A journal is composed of up to 512 files. 511 files are usable files and one file is reserved for depleted states.

-

The total memory used by the journal is limited to 1GB by default (and a maximum of 64GB). A flash journal is automatically used if the total memory of the journal exceeds the configured limit.

To configure a RAM journal resource manager, add a <ramjournal-manager> element within a <journaling-config> element and define any subelements that are to be overridden. The following example demonstrates overriding RAM journal subelements:

<?xml version='1.0'?>

<coherence xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config

coherence-operational-config.xsd">

<cluster-config>

<journaling-config>

<ramjournal-manager>

<maximum-value-size>64K</maximum-value-size>

<maximum-size system-property="coherence.ramjournal.size">2G</maximum-size>

</ramjournal-manager>

</journaling-config>

</cluster-config>

</coherence>

Parent topic: Changing Journaling Behavior

Configuring the Flash Journal Resource Manager

The <flashjournal-manager> element is used to configure flash journal behavior. The following list summarizes the default characteristics of a flash journal. See flashjournal-manager.

-

Binary values are limited by default to 64MB.

-

An individual buffer (a journal file) is limited by default to 2GB (and maximum 4GB).

-

A journal is composed of up to 512 files. 511 files are usable files and one file is reserved for depleted states. A journal is limited by default to 1TB, with a theoretical maximum of 2TB.

-

A journal has a high journal size of 11GB by default. The high size determines when to start removing stale values from the journal. This is not a hard limit on the journal size, which can still grow to the maximum file count (512).

-

Keys remain in memory in a compressed format. For values, only the unwritten data (being queued or asynchronously written) remains in memory. When sizing the heap, a reasonable estimate is to allow 50 bytes for each entry to hold key data (this is true for both RAM and Flash journals) and include additional space for the buffers (16MB). The entry size is increased if expiry or eviction is configured.

-

A flash journal is automatically used as overflow when the capacity of the RAM journal is reached. The flash journal can be disabled by setting the maximum size of the flash journal to 0, which means journaling exclusively uses a RAM journal.

To configure a flash journal resource manager, add a <flashjournal-manager> element within a <journaling-config> element and define any subelements that are to be overridden. The following example demonstrates overriding flash journal subelements:

<?xml version='1.0'?>

<coherence xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config

coherence-operational-config.xsd">

<cluster-config>

<journaling-config>

<flashjournal-manager>

<maximum-size>100G</maximum-size>

<directory>/coherence_storage</directory>

</flashjournal-manager>

</journaling-config>

</cluster-config>

</coherence>Note:

The directory specified for storing journal files must exist. If the directory does not exist, a warning is logged and the default temporary file directory, as designated by the JVM, is used.

Parent topic: Changing Journaling Behavior

Using Asynchronous Backup

Asynchronous backup is typically used to increase client performance. However, applications that use asynchronous backup must handle the possible effects on data integrity. Specifically, cache operations may complete before backup operations complete (successfully or unsuccessfully) and backup operations may complete in any order. Consider using asynchronous backup if an application does not require backups (that is, data can be restored from a system of record if lost) but the application still wants to offer fast recovery in the event of a node failure.

Note:

The use of asynchronous backups together with rolling restarts requires the use of the shutdown method to perform an orderly shut down of cluster members instead of the stop method or kill -9. Otherwise, a member may shutdown before asynchronous backups are complete. The shutdown method guarantees that all updates are complete.

To enable asynchronous backup for a distributed cache, add an <async-backup> element, within a <distributed-scheme> element, that is set to true. For example:

<distributed-scheme> ... <async-backup>true</async-backup> ... </distributed-scheme>

To enable asynchronous backup for all instances of the distributed cache service type, override the partitioned cache service's async-backup initialization parameter in an operational override file. For example:

<?xml version='1.0'?>

<coherence xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config

coherence-operational-config.xsd">

<cluster-config>

<services>

<service id="3">

<init-params>

<init-param id="27">

<param-name>async-backup</param-name>

<param-value

system-property="coherence.distributed.asyncbackup">

false

</param-value>

</init-param>

</init-params>

</service>

</services>

</cluster-config>

</coherence>

The coherence.distributed.asyncbackup system property is used to enable asynchronous backup for all instances of the distributed cache service type instead of using the operational override file. For example:

-Dcoherence.distributed.asyncbackup=true

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Using the Read Locator

Currently Coherence requests are serviced by the primary owner of the

associated partition(s) (ignoring the client side caches NearCache and

ContinuousQueryCache). Coherence 14.1.1.2206 introduces the read-locator feature. Read locator allows for certain

requests to be targeted to non-primary partition owners (backups) to balance request load or

reduce latency.

Currently only NamedMap.get and NamedMap.getAll

(see Interface NamedMap) requests support this

feature. If the application chooses to target a non-primary partition owner, then there

is an implied tolerance for stale reads. This may be possible as the primary (or other

backups) process future/in-flight changes while the targeted member that performed the

read has not.

read-locator for a cache or service by using the cache

configuration, as shown below:

...

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>example-distributed</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedCache</service-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<read-locator>closest</read-locator>

</backing-map-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme>

...The following read-locator values are supported:

primary- (default) target the request to the primary only.closest- find the 'closest' owner based on the member, machine, rack, or site information for each member in the partition’s ownership chain (primary and backups).random- pick a random owner in the partition’s ownership chain.random-backup- pick a random backup owner in the partition’s ownership chain.class-scheme- provide your own implementation that receives the ownership chain and returns the member to the target.

For information about the client side caches NearCache and

ContinuousQueryCache, see Understanding Near Caches and Using Continuous Query Caching.

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Scheduling Backups

Internally this still results in n backup messages being created for

n write requests, which has a direct impact on write

throughput. To improve the write throughput, Coherence 14.1.1.2206 introduces "Scheduled" (or periodic) backups. This feature

allows the number of backup messages to be <n.

The current async-backup XML element (see Using Asynchronous Backup) has been augmented to accept more than a simple true|false

value and now supports a time-based value. This allows applications to suggest a

soft target of how long they are willing to tolerate stale backups. At runtime

Coherence may decide to accelerate backup synchronicity, or increase the staleness

based on the primary write throughput.

Note:

You must be careful when choosing the backup interval because there is a potential for losing updates in the event of losing a primary partition owner. All the updates waiting to be sent by that primary owner will not be reflected when the corresponding backup owner is restored and becomes the primary owner.Example 14-1 Example Configuration

...

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>example-distributed</scheme-name>

<service-name>DistributedCache</service-name>

<autostart>true</autostart>

<async-backup>10s</async-backup>

</distributed-scheme>

...-Dcoherence.distributed.asyncbackup=10sParent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Using Asynchronous Persistence

This allows writes to not be blocked on latency of writing to the underlying device, however does introduce a potential to lose writes. This mode is primarily viable when data can be replenished and the persisted data provides an optimized means to recover data.

You can enable asynchronous persistence by specifying the <persistence-mode> of the <persistence-environment> as active-async.

There is an out-of-the-box persistence environment that specifies this mode and can be referred to by customer applications by either:

- Specifying the JVM argument:

-Dcoherence.distributed.persistence.mode=active-async

Note:

This is used by all distributed services. - Referring to the

default-active-asyncpersistence environment in the cache configuration:See persistence.

<distributed-scheme> ….….…. <persistence> <environment>default-active-async</environment> </persistence> ….….…. </distributed-scheme>Note:

This allows you to selectively choose which services have persistence enabled.

You can also define a new <persistence-environment> element in the operational configuration file and specify the mode to be active-async to enable asynchronous persistence. See persistence-environment.

For example:

<persistence-environment id="async-environment">

<persistence-mode>active-async</persistence-mode>

<active-directory>/tmp/store-bdb-active</active-directory>

<snapshot-directory>/tmp/store-bdb-snapshot</snapshot-directory>

<trash-directory>/tmp/store-bdb-trash</trash-directory>

</persistence-environment>To use this environment in the nominated distributed-schemes, it must be referenced in the cache configuration.

For example:

<distributed-scheme>

….….….

<persistence>

<environment>async-environment</environment>

</persistence>

….….….

</distributed-scheme>

Note:

With asynchronous persistence, it is possible to have data loss if the cluster is shutdown before the persistent transaction is complete.To ensure that there is no data loss during a controlled shutdown, customers can leverage the service suspend feature. A service is only considered suspended once all data is fully written, including asynchronous persistence tasks, entries in the write-behind queue of a readwrite-backing-map, and so on.

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Using Persistent Backups

Coherence 14.1.1.2206 adds a new persistence mode that stores backup partitions on disk as additional copies of persisted primary ones.

This section includes the following topics:

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

About Persistent Backups

In active persistence mode, Coherence eagerly persists primary partitions to disk to permit recovery of data when a complete shutdown (voluntary or not) occurs.

In this mode and at runtime, every cache mutation is saved to disk in a synchronous manner. That is, every operation that waits for a cache update to complete before returning control to the client, also waits for persistence to complete.

While active persistence increases reliability, there are still conditions that could cause data to be lost. For example, when members do not save in the same location, and when some locations become inaccessible or corrupted.

To alleviate this issue, a new mode "active-backup", also persists the backup partitions to disk. This operation is always asynchronous so as to have as little impact on performance as possible.

In this mode, when primary partitions are not found during recovery, backup ones are looked for and used instead. The simplest case is that of a cluster where two storage-enabled members are running on two difference machines with each having its own storage. In this topology, they each divide almost equally into primary and backup partitions: member 1 will own primary partition P1, P2, and P3, and backup partitions B4, B5, B6, and B7. Member 2 will own P4, P5, P6, and P7 as well as B1, B2, and B3.

In the case, where both members are lost, but only one storage can be recovered, you can restart any member by using a single surviving storage and recover the entire set of data. In the active (non-backup) mode, only about half of the data set would be recovered in the same situation.

Parent topic: Using Persistent Backups

Configuring Active Persistence Mode

coherence.distributed.persistence.mode. For

example:-Dcoherence.distributed.persistence.mode=active-backupOptionally, you can configure a backup location to store backup partitions using

<backup-directory/> in the Coherence operational override

file. Otherwise, they are stored in the path specified by

coherence.distributed.persistence.base.dir (or its default) followed by

'/backup'.

<persistence-environments>

<persistence-environment id="active-backup-environment">

<persistence-mode system-property="coherence.persistence.mode">active-backup</persistence-mode>

<active-directory system-property="coherence.persistence.active.dir">/store-bdb-active</active-directory>

<backup-directory system-property="coherence.persistence.backup.dir">/store-bdb-backup</backup-directory>

<snapshot-directory system-property="coherence.persistence.snapshot.dir">/store-bdb-snapshot</snapshot-directory>

<trash-directory system-property="coherence.persistence.trash.dir">/store-bdb-trash</trash-directory>

</persistence-environment>

</persistence-environments>Parent topic: Using Persistent Backups

Performance Considerations

While runtime performance impact is minimal, there are still performance considerations to account for. Since there are more persistence files created, start-up and recovery times can be affected, especially if the number of partitions configured is large. To minimize the impact on start-up/recovery times, you can use recovery quorum.

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>partitioned</scheme-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<partitioned>true</partitioned>

<read-write-backing-map-scheme>

<internal-cache-scheme>

<local-scheme>

</local-scheme>

</internal-cache-scheme>

</read-write-backing-map-scheme>

</backing-map-scheme>

<partitioned-quorum-policy-scheme>

<recover-quorum>3</recover-quorum>

</partitioned-quorum-policy-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme>In the above example, you can set the recover-quorum value to the desired number of members in the cluster, which causes recovery to occur only when that number of members has joined. Instead of recovery taking place at the same time as distribution, it occurs only once and completes faster.

Parent topic: Using Persistent Backups

Using Delta Backup

Delta backup uses a compressor that compares two in-memory buffers containing an old and a new value and produces a result (called a delta) that can be applied to the old value to create the new value. Coherence provides standard delta compressors for POF and non-POF formats. Custom compressors can also be created and configured as required.

This section includes the following topics:

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

Enabling Delta Backup

Delta backup is only available for distributed caches and is disabled by default. Delta backup is enabled either individually for each distributed cache or for all instances of the distributed cache service type.

To enable delta backup for a distributed cache, add a <compressor> element, within a <distributed-scheme> element, that is set to standard. For example:

<distributed-scheme> ... <compressor>standard</compressor> ... </distributed-scheme>

To enable delta backup for all instances of the distributed cache service type, override the partitioned cache service's compressor initialization parameter in an operational override file. For example:

<?xml version='1.0'?>

<coherence xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://xmlns.oracle.com/coherence/coherence-operational-config

coherence-operational-config.xsd">

<cluster-config>

<services>

<service id="3">

<init-params>

<init-param id="22">

<param-name>compressor</param-name>

<param-value

system-property="coherence.distributed.compressor">

standard</param-value>

</init-param>

</init-params>

</service>

</services>

</cluster-config>

</coherence>

The coherence.distributed.compressor system property is used to enable delta backup for all instances of the distributed cache service type instead of using the operational override file. For example:

-Dcoherence.distributed.compressor=standard

Parent topic: Using Delta Backup

Enabling a Custom Delta Backup Compressor

To use a custom compressor for performing delta backup, include an <instance> subelement and provide a fully qualified class name that implements the DeltaCompressor interface. See instance. The following example enables a custom compressor that is implemented in the MyDeltaCompressor class.

<distributed-scheme>

...

<compressor>

<instance>

<class-name>package.MyDeltaCompressor</class-name>

</instance>

</compressor>

...

</distributed-scheme>

As an alternative, the <instance> element supports the use of a <class-factory-name> element to use a factory class that is responsible for creating DeltaCompressor instances, and a <method-name> element to specify the static factory method on the factory class that performs object instantiation. The following example gets a custom compressor instance using the getCompressor method on the MyCompressorFactory class.

<distributed-scheme>

...

<compressor>

<instance>

<class-factory-name>package.MyCompressorFactory</class-factory-name>

<method-name>getCompressor</method-name>

</instance>

</compressor>

...

</distributed-scheme>

Any initialization parameters that are required for an implementation can be specified using the <init-params> element. The following example sets the iMaxTime parameter to 2000.

<distributed-scheme>

...

<compressor>

<instance>

<class-name>package.MyDeltaCompressor</class-name>

<init-params>

<init-param>

<param-name>iMaxTime</param-name>

<param-value>2000</param-value>

</init-param>

</init-params>

</instance>

</compressor>

...

</distributed-scheme>

Parent topic: Using Delta Backup

Integrating Caffeine

This section includes the following topics:

- About Caffeine

Caffeine is a high performance, near optimal caching library. It improves upon Coherence’s standard local cache by offering better read and write concurrency, as well as a higher hit rate. - Using Caffeine

- Configuring Caffeine

Parent topic: Implementing Storage and Backing Maps

About Caffeine

Caffeine is a high performance, near optimal caching library. It improves upon Coherence’s standard local cache by offering better read and write concurrency, as well as a higher hit rate.

Caffeine implements an adaptive eviction policy that can achieve a significantly higher hit rate across a large variety of workloads. You can leverage this feature to either reduce latencies or maintain the same performance with smaller caches. This may allow for decreasing the operational costs due to requiring fewer resources for the same workload. For more information, see Caffeine

The adaptive nature of this policy, nicknamed W-TinyLFU, allows it to stay robustly performant despite changes in the runtime workload. For more information, see Adaptive Software Cache Management and TinyLFU: A Highly Efficient Cache Admission Policy. Those changes may be caused by variations in the external request pattern or differences caused by the application’s evolution. This self-optimizing, O(1) algorithm avoids the need to manually analyze the application and tune the cache to a more optimal eviction policy.

The following table shows cache hit rates for Caffeine’s W-TinyLFU compared to other commonly used cache eviction policies, for various types of workloads:

Table 14-1 Cache Hit Rates for Caffeine’s W-TinyLFU vs. Other Common Cache Eviction Policies

| Workload | W-TinyLFU | Hybrid | LRU | LFU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

An analytical loop |

32.7% |

2.6% |

1.0% |

1.4% |

|

Blockchain mining |

32.3% |

12.1% |

33.3% |

0.0% |

|

OLTP |

40.2% |

15.4% |

33.2% |

9.6% |

|

Search |

42.5% |

31.3% |

12.0% |

29.3% |

|

Database |

44.8% |

37.0% |

20.2% |

39.1% |

Parent topic: Integrating Caffeine

Using Caffeine

Caffeine is integrated tightly into Coherence and is almost as easy to use as any of the built-in backing map implementations that Coherence provides. The only difference is that Caffeine requires you to add a dependency on Caffeine to your project’s POM file, as it is defined as an optional dependency within Coherence POM.

<dependency>

<groupId>com.github.ben-manes.caffeine</groupId>

<artifactId>caffeine</artifactId>

<version>${caffeine.version}</version>

</dependency>The supported Caffeine versions are 3.1.0 or higher.

Parent topic: Integrating Caffeine

Configuring Caffeine

After you have added the dependency, Caffeine is as easy to use as a standard local cache implementation.

Coherence provides caffeine-scheme configuration element, which can be

used anywhere the local-scheme element is currently used: standalone,

as a definition of a local cache scheme; within the distributed-scheme

element as a backing-map for a partitioned cache; or within the

near-scheme element as a front-map.

<caffeine-scheme>

<scheme-name>caffeine-local-scheme</scheme-name>

</caffeine-scheme><distributed-scheme>

<scheme-name>caffeine-distributed-scheme</scheme-name>

<backing-map-scheme>

<caffeine-scheme />

</backing-map-scheme>

<autostart>true</autostart>

</distributed-scheme><near-scheme>

<scheme-name>caffeine-near-scheme</scheme-name>

<front-scheme>

<caffeine-scheme />

</front-scheme>

<back-scheme>

<distributed-scheme>

<scheme-ref>my-dist-scheme</scheme-ref>

</distributed-scheme>

</back-scheme>

</near-scheme>You can configure each of the caffeine-scheme elements the same way

local-scheme is configured, by specifying one or more of the

following child elements:

Table 14-2 Child Elements Within the caffeine-scheme Elements

| Configuration Element | Description |

|---|---|

|

|

The name of this scheme, which you can reference elsewhere in the configuration file. |

|

|

The reference (by name) to a |

|

|

The name of the custom class that extends

|

|

|

The name of the scope. |

|

|

The name of the service. |

|

|

The arguments to pass to the |

|

|

The maximum amount of data the cache should be allowed to hold before the eviction occurs. |

|

|

The unit calculator to use, typically one of the following:

|

|

|

Sometimes used in combination with a |

|

|

The amount of time from last update that the entries are kept in cache before being discarded. |

|

|

A |

All of the configuration elements above are optional, but you will typically want to set

either high-units or expiry-delay (or both) to limit

cache based on either size or time-to-live (TTL).

If neither is specified, the cache size is limited only by available memory, and you can

specify the TTL explicitly by using the NamedCache.put(key, value, ttl)

method or by calling BinaryEntry.expire within an entry processor.

There is nothing wrong if you do not want to limit the cache by either size or time; you may still benefit from using Caffeine in those situations, especially under high concurrent load, due to its lock-free implementation.

Finally, when using Caffeine as a backing map for a partitioned cache, you will likely

want to configure unit-calculator to BINARY, so you

can set the limits and observe cache size (through JMX or Metrics) in bytes instead of

the number of entries in the cache.

Parent topic: Integrating Caffeine