SPARC Behavior and Implementation

This chapter discusses issues related to the floating-point units used in SPARC-based workstations and describes a way to determine which code generation flags are best suited for a particular workstation.

B.1 Floating-Point Hardware

This section lists a number of SPARC processors and describes the instruction sets and exception handling features they support.

The following tables list the hardware floating-point implementations used by recent SPARC systems:

|

|

Although it is not supported, programs compiled with Oracle Solaris Studio 12.4 on Oracle Solaris 10 Update 10 or earlier Oracle Solaris releases often run on older SPARC systems that support earlier Oracle Solaris Studio releases. To create an executable to test on such platforms, try compiling with the following options:

–m32 –xarch=generic –xchip=generic

For a supported solution, compile on the earliest Oracle Solaris release that you need to use and compile with the latest Oracle Solaris Studio version supported on that Oracle Solaris release.

The last column in the preceding table shows the compiler flags to use to obtain the fastest code for each FPU. These flags control two independent attributes of code generation: the –xarch flag determines the instruction set the compiler may use, and the –xchip flag determines the assumptions the compiler will make about a processor's performance characteristics in scheduling the code. A program compiled with the default –xarch or with the explicit –xarch=sparc runs on any SPARC-based system listed above, although it might not take full advantage of the features of later processors. Likewise, a program compiled with a particular –xchip value runs on any SPARC-based system that supports the instruction set specified with –xarch, but it might run more slowly on systems with processors other than the one specified.

The UltraSPARC I, UltraSPARC II, UltraSPARC IIe, UltraSPARC IIi, UltraSPARC III, UltraSPARC IIIi, UltraSPARC IV, and UltraSPARC IV+ floating-point units implement the floating-point instruction set defined in the SPARC Architecture Manual Version 9 except for the quad precision instructions; in particular, they provide 32 double precision floating-point registers. Compiling with –xarch=sparc enables the compiler to use all these features. These processors also provide extensions to the standard instruction set. Successive generations of these additional instructions are enabled by these –xarch values:

-

sparcvis

-

sparcvis2

-

sparcvis2

-

sparc4

-

sparc5

Many of these additional instructions are rarely generated automatically by the compilers, but they can be used in assembly code.

The –xarch and –xchip options can be specified simultaneously using the –xtarget macro option. The –xtarget flag simply expands to a suitable combination of –xarch, –xchip, and –xcache flags. The default code generation option is -xtarget=generic. See the cc(1), CC(1), and f95(1) man pages and the Oracle Solaris Studio 12.4: Fortran User’s Guide , Oracle Solaris Studio 12.4: C User’s Guide , and Oracle Solaris Studio 12.4: C++ User’s Guide compiler manuals for more information including a complete list of –xarch, –xchip, and –xtarget values.

B.1.1 Floating-Point Status Register and Queue

All SPARC floating-point units, regardless of which version of the SPARC architecture they implement, provide a floating-point status register (FSR) that contains status and control bits associated with the FPU. All SPARC FPUs that implement deferred floating-point traps provide a floating-point queue (FQ) that contains information about currently executing floating-point instructions. The FSR can be accessed by user software to detect floating-point exceptions that have occurred and to control rounding direction, trapping, and nonstandard arithmetic modes. The FQ is used by the operating system kernel to process floating-point traps and is normally invisible to user software.

Software accesses the floating-point status register via STFSR and LDFSR instructions that store the FSR in memory and load it from memory, respectively. In SPARC assembly language, these instructions are written as follows:

st %fsr, [addr] ! store FSR at specified address

ld [addr], %fsr ! load FSR from specified address

The inline template file libm.il located in the directory containing the libraries supplied with the Sun Studio compilers contains examples showing the use of STFSR and LDFSR instructions.

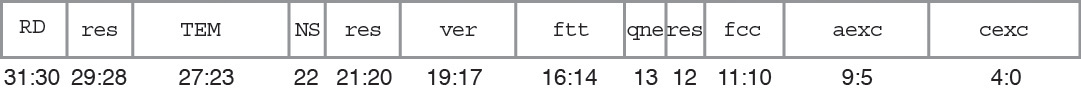

The following figure shows the layout of bit fields in the floating-point status register.

Figure B-1 SPARC Floating-Point Status Register

In versions 7 and 8 of the SPARC architecture, the FSR occupies 32 bits as shown. In version 9, the FSR is extended to 64 bits, of which the lower 32 match the figure; the upper 32 are largely unused, containing only three additional floating-point condition code fields.

In the figure, res refers to bits that are reserved, ver is a read-only field that identifies the version of the FPU, and ftt and qne are used by the system when it processes floating-point traps. The remaining fields are described in the following table

|

The RM field holds two bits that specify the rounding direction for floating-point operations. The NS bit enables nonstandard arithmetic mode on SPARC FPUs that implement it; on others, this bit is ignored. The fcc field holds floating-point condition codes generated by floating-point compare instructions and used by branch and conditional move operations. Finally, the TEM, aexc, and cexc fields contain five bits that control trapping and record accrued and current exception flags for each of the five IEEE 754 floating-point exceptions. These fields are subdivided as shown in the following table.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

(The symbols NV, OF, UF, DZ, and NX above stand for the invalid operation, overflow, underflow, division-by-zero, and inexact exceptions respectively.)

B.1.2 Special Cases Requiring Software Support

In most cases, SPARC floating-point units execute instructions completely in hardware without requiring software support. There are four situations, however, when the hardware will not successfully complete a floating-point instruction:

The floating-point unit is disabled.

The instruction is not implemented by the hardware, such as quad precision instructions on any SPARC FPU.

The hardware is unable to deliver the correct result for the instruction's operands.

The instruction would cause an IEEE 754 floating-point exception and that exception's trap is enabled.

In each situation, the initial response is the same: the process traps to the system kernel, which determines the cause of the trap and takes the appropriate action. The term “trap” refers to an interruption of the normal flow of control. In the first three situations, the kernel emulates the trapping instruction in software. Note that the emulated instruction can also incur an exception whose trap is enabled.

In the first three situations above, if the emulated instruction does not incur an IEEE floating-point exception whose trap is enabled, the kernel completes the instruction. If the instruction is a floating-point compare, the kernel updates the condition codes to reflect the result; if the instruction is an arithmetic operation, it delivers the appropriate result to the destination register. It also updates the current exception flags to reflect any (untrapped) exceptions raised by the instruction, and it “or”s those exceptions into the accrued exception flags. It then arranges to continue execution of the process at the point at which the trap was taken.

When an instruction executed by hardware or emulated by the kernel software incurs an IEEE floating-point exception whose trap is enabled, the instruction is not completed. The destination register, floating-point condition codes, and accrued exception flags are unchanged, the current exception flags are set to reflect the particular exception that caused the trap, and the kernel sends a SIGFPE signal to the process.

The following pseudo-code summarizes the handling of floating-point traps. Note that the aexc field can normally only be cleared by software.

FPop provokes a trap;

if trap type is fp_disabled, unimplemented_FPop, or

unfinished_FPop then

emulate FPop;

texc = all IEEE exceptions generated by FPop;

if (texc and TEM) = 0 then

f[rd] = fp_result; // if fpop is an arithmetic op

fcc = fcc_result; // if fpop is a compare

cexc = texc;

aexc = (aexc or texc);

else

cexc = trapped IEEE exception generated by FPop;

throw SIGFPE;

A program will encounter severe performance degradation when many floating-point instructions must be emulated by the kernel. The relative frequency with which this happens can depend on several factors including the type of trap.

Under normal circumstances, the fp_disabled trap should occur only once per process. The system kernel disables the floating-point unit when a process is first started, so the first floating-point operation executed by the process will cause a trap. After processing the trap, the kernel enables the floating-point unit, and it remains enabled for the duration of the process. (It is possible to disable the floating-point unit for the entire system, but this is not recommended and is done only for kernel or hardware debugging purposes.)

An unimplemented_FPop trap occurs any time the floating-point unit encounters an instruction it does not implement. Since most current SPARC floating-point units implement at least the instruction set defined by the SPARC Architecture Manual Version 8, except for the quad precision instructions, and the Oracle Solaris Studio compilers do not generate quad precision instructions, this type of trap should not occur on most systems compiled with –xarch=sparc.

The remaining two trap types, unfinished_FPop and trapped IEEE exceptions, are usually associated with special computational situations involving NaNs, infinities, and subnormal numbers.

B.1.2.1 IEEE Floating-Point Exceptions, NaNs, and Infinities

When a floating-point instruction encounters an IEEE floating-point exception whose trap is enabled, the instruction is not completed. Instead the system delivers a SIGFPE signal to the process. If the process has established a SIGFPE signal handler, that handler is invoked, and otherwise, the process aborts. Since trapping is most often enabled for the purpose of aborting the program when an exception occurs, either by invoking a signal handler that prints a message and terminates the program or by resorting to the system default behavior when no signal handler is installed, most programs do not incur many trapped IEEE floating-point exceptions. As described in Chapter 4, Exceptions and Exception Handling, however, it is possible to arrange for a signal handler to supply a result for the trapping instruction and continue execution. Note that severe performance degradation can result if many floating-point exceptions are trapped and handled in this way.

Some SPARC floating-point units will also trap on at least some cases involving infinite or NaN operands or IEEE floating-point exceptions even when trapping is disabled or an instruction would not cause an exception whose trap is enabled. This happens when the hardware does not support such special cases. Instead it generates an unfinished_FPop trap and leaves the kernel emulation software to complete the instruction. Different SPARC FPUs vary as to the conditions that result in an unfinished_FPop trap. For example, most early SPARC FPUs trap on all IEEE floating-point exceptions regardless of whether trapping is enabled, while UltraSPARC FPUs can trap pessimistically when a floating-point exception's trap is enabled and the hardware is unable to determine whether an instruction would raise that exception.But any recent SPARC processors handle all exceptional cases in hardware and never generate an unfinished_FPop traps.

Since most unfinished_FPop traps occur in conjunction with floating-point exceptions, a program can avoid incurring an excessive number of these traps by employing exception handling: testing the exception flags, trapping and substituting results, or aborting on exceptions. Take care to balance the cost of handling exceptions with that of allowing exceptions to result in unfinished_FPop traps.

B.1.2.2 Subnormal Numbers and Nonstandard Arithmetic

The most common situations in which some SPARC floating-point units will trap with an unfinished_FPop involve subnormal numbers. Many older SPARC floating-point units will trap whenever a floating-point operation involves subnormal operands or must generate a nonzero subnormal result, i.e., a result that incurs gradual underflow. Because underflow is somewhat rare but difficult to program around, and because the accuracy of underflowed intermediate results often has little effect on the overall accuracy of the final result of a computation, the SPARC architecture defines a nonstandard arithmetic mode that provides a way for a user to avoid the performance degradation associated with unfinished_FPop traps involving subnormal numbers.

The SPARC architecture does not precisely define nonstandard arithmetic mode. It merely states that when this mode is enabled, processors that support it might produce results that do not conform to the IEEE 754 standard. However, all existing SPARC implementations that support this mode use it to disable gradual underflow, replacing all subnormal operands and results with zero.

Not all SPARC implementations provide a nonstandard mode. SPARC implementations that do not support this mode simply ignore it, so numerical and exception results are the same in nonstandard more. Gradual underflow incurs no performance loss on these processors.

To determine whether gradual underflows are affecting the performance of a program, you should first determine whether underflows are occurring at all and then check how much system time is used by the program. To determine whether underflows are occurring, you can use the math library function ieee_retrospective() to see if the underflow exception flag is raised when the program exits. Fortran programs call ieee_retrospective() by default. C and C++ programs need to call ieee_retrospective() explicitly prior to exit. If any underflows have occurred, ieee_retrospective() prints a message similar to the following:

Note: IEEE floating-point exception flags raised: Inexact; Underflow; See the Numerical Computation Guide, ieee_flags(3M)

If the program encounters underflows, you might want to determine how much system time the program is using by timing the program execution with the time command:

demo% /bin/time myprog > myprog.output real 305.3 user 32.4 sys 271.9

If the system time, the third figure of the previous output, is unusually high, multiple underflows might be the cause. If so, and if the program does not depend on the accuracy of gradual underflow, you can enable nonstandard mode for better performance.

There are two ways to do this. First, you can compile with the –fns flag, which is implied as part of the macros –fast and –fnonstd, to enable nonstandard mode at program startup. Second, the value-added math library libsunmath provides two functions to enable and disable nonstandard mode, respectively: calling nonstandard_arithmetic() enables nonstandard mode (if it is supported), while calling standard_arithmetic() restores IEEE behavior. The C and Fortran syntax for calling these functions is as follows:

|

| Caution - Since nonstandard arithmetic mode defeats the accuracy benefits of gradual underflow, you should use it with caution. For more information about gradual underflow, see Chapter 2, IEEE Arithmetic. |

B.1.2.3 Nonstandard Arithmetic and Kernel Emulation

On SPARC floating-point units that implement nonstandard mode, enabling this mode causes the hardware to treat subnormal operands as zero and flush subnormal results to zero. The kernel software that is used to emulate trapped floating-point instructions, however, does not implement nonstandard mode, in part because the effect of this mode is undefined and implementation-dependent and because the added cost of handling gradual underflow is negligible compared to the cost of emulating a floating-point operation in software.

If a floating-point operation that would be affected by nonstandard mode is interrupted (for example, it has been issued but not completed when a context switch occurs or another floating-point instruction causes a trap), it will be emulated by kernel software using standard IEEE arithmetic. Thus, under unusual circumstances, a program running in nonstandard mode might produce slightly varying results depending on system load. This behavior has not been observed in practice. It would affect only those programs that are very sensitive to whether one particular operation out of millions is executed with gradual underflow or with abrupt underflow.

B.2 fpversion(1) Function: Finding Information About the FPU

The fpversion utility distributed with the compilers identifies the installed CPU and estimates the processor and system bus clock speeds. fpversion determines the CPU and FPU types by interpreting the identification information stored by the CPU and FPU. It estimates their clock speeds by timing a loop that executes simple instructions that run in a predictable amount of time. The loop is executed many times to increase the accuracy of the timing measurements. For this reason, fpversion is not instantaneous. It can take several seconds to run.

fpversion also reports the best –xtarget code generation option to use for the host system.

On a T4-2 server, fpversion displays information similar to the following. There might be variations due to differences in timing or machine configuration.

demo% fpversion A SPARC-based CPU is available. Kernel says CPU's clock rate is 1500.0 MHz. Kernel says main memory's clock rate is 150.0 MHz. Sun-4 floating-point controller version 0 found. An UltraSPARC chip is available. Use "-xtarget=T4 -xcache=16/32/4/8:128/32/8/8:4096/64/16/64" code-generation option. Hostid = hardware_host_id

See the fpversion(1) manual page for more information.